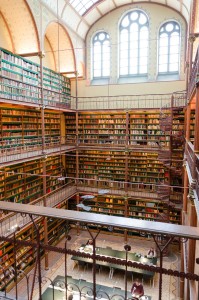

The Story Bazaar is fond of libraries, as well as the stories within them. It is an Amsterdam Library which forms the backdrop for the web-site after all. Earlier this week I went to see some of the remains of one of the very first libraries which ever existed. Indeed, it can claim to be the first, large library. It was collected by King Ashurbanipal, the last King of Assyria (c.688 – 630 BCE) in Nineveh, his capital ( now Kouyunjik in modern-day Iraq ). It was also the inspiration for Alexander the Great to one day found his own library, the famous Library of Alexandria.

The Story Bazaar is fond of libraries, as well as the stories within them. It is an Amsterdam Library which forms the backdrop for the web-site after all. Earlier this week I went to see some of the remains of one of the very first libraries which ever existed. Indeed, it can claim to be the first, large library. It was collected by King Ashurbanipal, the last King of Assyria (c.688 – 630 BCE) in Nineveh, his capital ( now Kouyunjik in modern-day Iraq ). It was also the inspiration for Alexander the Great to one day found his own library, the famous Library of Alexandria.

Ashurbanipal’s Library is estimated to have contained tens of thousands of texts, written or inscribed on leather scrolls, papyri, soft wax and hard clay tablets,  covering all forms of knowledge. There were historical inscriptions, legislative, financial and legal texts, medical, literary and lexical texts and many texts of a divinatory, magical or astrological nature ( a particular interest of the King ). The tablets are written in several different types of cuneiform script and there seems to have been some clever organisation within the Library e.g. it is thought that agricultural texts were written on round tablets, while other subjects had different shaped tablets.

covering all forms of knowledge. There were historical inscriptions, legislative, financial and legal texts, medical, literary and lexical texts and many texts of a divinatory, magical or astrological nature ( a particular interest of the King ). The tablets are written in several different types of cuneiform script and there seems to have been some clever organisation within the Library e.g. it is thought that agricultural texts were written on round tablets, while other subjects had different shaped tablets.

One tablet is the so-called ‘Flood Tablet’ inscribed with part of the Epic of Gilgamesh, a collection of stories and poems which were first told in Sumer about 2,100 BCE. Ashurbanipal’s was the later, standard version of this, the stories drawn together into probably the oldest ‘great work’ of literature and written in a dialect of Akkadian used specifically for literary purposes. It is one of the earliest ‘flood myths’ pre-dating the story of Noah and his Ark by about a thousand years.

One tablet is the so-called ‘Flood Tablet’ inscribed with part of the Epic of Gilgamesh, a collection of stories and poems which were first told in Sumer about 2,100 BCE. Ashurbanipal’s was the later, standard version of this, the stories drawn together into probably the oldest ‘great work’ of literature and written in a dialect of Akkadian used specifically for literary purposes. It is one of the earliest ‘flood myths’ pre-dating the story of Noah and his Ark by about a thousand years.

Unfortunately much of the Library did not survive. Nineveh and the palace complex was destroyed in 612 BCE by a coalition of Babylonians, Scythians and Medes who torched the palace. The fire would have been visible for miles as all that was combustible, including much of the contents of the Library, went up in smoke. A precursor to the burning of Persepolis, perhaps, and, eventually, of the Library of Alexandria too. This fire, however, preserved as well as destroyed. The clay tablets and boards were baked, their surfaces becoming glass-like in the high temperatures of the blaze.

The extant texts, numbering approximately 30,000 pieces of tablets and writing boards in the British Museum, were subsequently discovered in the 1850s by Sir Austen Henry Layard and Hormuzd Rassam. The latter’s life is worthy of a story all of its own – he went from hired pay-clerk on Layard’s first dig, to Magdalen College, Oxford. He led his own expeditions, with the backing of the British Museum, and then became a British Ambassador. He and his family eventually settled in Brighton, becoming a respected and revered Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society, a member of the Victoria Institute ( he had met the Queen ) and recipient of the Brazza Prize from the Italian Royal Academy of Sciences.

Today, the Ashurbanipal Library Project, a long-term international project, set up in 2002 by the BM in partnership with the University of Mosul, is digitising and translating all the texts. The aim of the project is, ultimately, to gain a greater understanding of life in ancient Mesopotamia. Those texts already deciphered and translated are already available for investigation.

I will be writing further about Mesopotamia and early stories in a later post. In the meantime, if you enjoyed reading this article you might also enjoy Amazing Grace The Real Thing A Walk on the Wild Side From Gutenberg to Google

RSS – Posts

RSS – Posts